Photographie Ã⠠Paris Stereoview Paris Au Stereoscope

Is it possible, for the states who live in the 21st century, to imagine or – probably fifty-fifty more hard – understand what the Victorians saw in the Stereoscope? In 1980 literary theorist, philosopher and semiotician Roland Barthes, confronted to a similar result, exclaimed, "I want a History of Looking".1 Roland Barthes, La chambre claire: note sur la photographie. Paris: Cahiers du cinéma: Gallimard: Le Seuil, 1980. Chapter 5. The book was translated into English language and published in 1981 under the title Camera Lucida: Reflexions on Photography. Ten years later, art critic and essayist Jonathan Crary was certain that "we volition never really know what the stereoscope looked like to a nineteenth-century viewer."2 Jonathan Cray, Techniques of the Observer: on Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT, 1990. Even when we were not specifically looking for them, we have been bombarded with pictures from an early historic period and we have seen, looked at, glanced at, stared at, scrutinised, millions of photographs, in albums, on print, on television, and, more recently, on the displays of our smartphones or computers. Can we erase all those photographs from our memory, forget nigh our image-based culture and get dorsum to the state of mind of a middle-class Victorian seeing their outset photo or viewing their kickoff binocular picture in a stereoscope? We tin at least endeavour.

A philosophical toy

Although invented every bit early every bit 1832 but merely known at the time to the pocket-size circle of friends of its creator, brilliant polymath Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875), the stereoscope was presented publicly on 21 June 1838 before the Royal Guild of London. On that twenty-four hour period Wheatstone read a paper entitled Contribution to the Physiology of Vision – Part the First. On some remarkable and hitherto unobserved phenomena of binocular vision. He also brought with him a rather crudely congenital device which he called a "stereoscope", a term he had coined himself from two Greek words meaning "solids I come across".

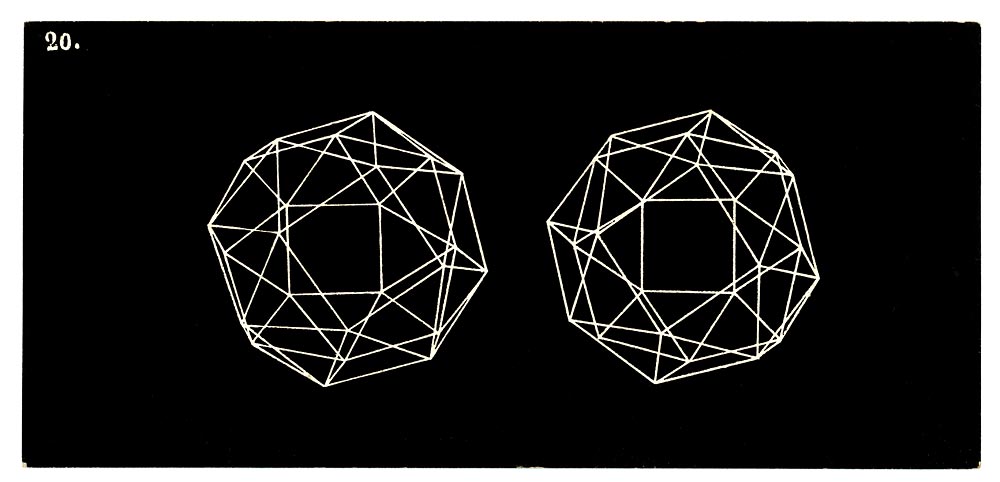

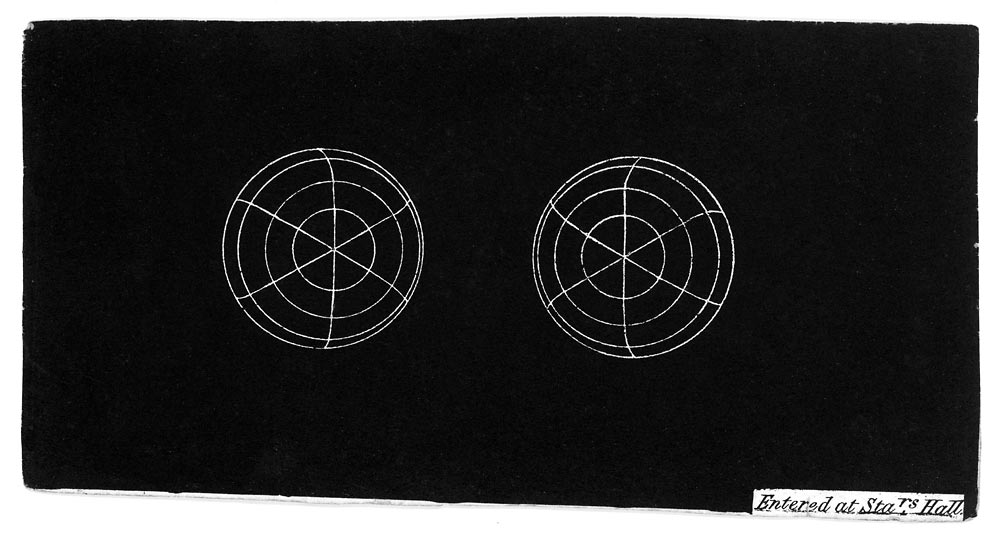

Wheatstone's stereoscope consisted of 2 mirrors joined by one of their edges and forming an bending of 90º. On either side of the mirrors and at an angle of 45º were two wooden boards on which images could be inserted or pinned. Those side boards could exist moved away from or closer to the mirrors by means of a wooden countless spiral, and that was it. Since photography had non yet been revealed to the world, Wheatstone could only illustrate his theory of vision with uncomplicated figures he had to draw himself or inquire someone to draw for him. The purpose of Wheatstone's stereoscope was to demonstrate that our perception of depth can be simulated by two flat perspectives of the same object as perceived by each of our optics and presented in such a way that only the left eye can run into the left image and the correct eye the other one. Even if photography had been known and so Wheatstone would probably have used the same outline drawings. His intention was to eliminate whatsoever other depth cues for "had either shading or colouring been introduced it might be supposed that the effect was wholly or in part due to these circumstances, whereas past leaving them out of consideration no room is left to doubt that the entire issue of relief is attributable to the simultaneous perception of the 2 monocular projections, 1 on each retina."3 Charles Wheatstone, Contribution to the Physiology of Vision – Part the First. On some remarkable and hitherto unobserved phenomena of binocular vision, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Social club of London, Vol. 128 (1838), pp. 376, paragraph iv. Wheatstone illustrated his newspaper with twelve of these outline figures, a couple of which accept survived to this mean solar day. The scientific globe welcomed his discovery "as one of the most curious and beautiful for its simplicity, in the entire range of experimental optics"4 The Archives, No. 567, 8 September 1838, p. 650. Those words were uttered by Sir John Herschel (1792-1871) and the stereoscope entered the physics laboratory. Information technology would well-nigh certainly had remained in that location had not photography been invented. Photography on metallic and on paper appeared in 1839 simply despite Wheatstone's early efforts at having photographs fabricated for his instrument by William Henry Fox Talbot, Henry Collen (paper), Hippolyte Fizeau and Antoine Claudet (metal), information technology wasn't before the Keen Exhibition of 1851 and the modifications brought to the original instrument by Sir David Brewster (1849) and optician Louis Jules Duboscq (1859) who replaced the mirrors with half lenses and made it more compact and portable, that the stereoscope became known to the full general public. When the London Exhibition closed its doors in November 1851 only the well-off could buy their daguerreotype portraits for the stereoscope or stereoscopic views on plate of the interior of the Crystal Palace. Everyone else had to exist content with series of lithographs featuring white outline geometrical subjects on a blackness groundwork which were published by Jules Duboscq in France and by Frederick Hale Holmes in United kingdom, some of them inspired past Wheatstone'southward original figures.

The stereoscope was no more so than some other philosophical toy, like the kaleidoscope or the phenakistiscope, used to illustrate the principles of binocular vision. Although these diagrams may seem fairly lame to us, they were of great interest to the Victorians whose e'er-curious mind was e'er trying to understand the world around them. They are too the first stereoscopic pictures they could afford and own, which fabricated them of import and precious.

Capturing depth and time

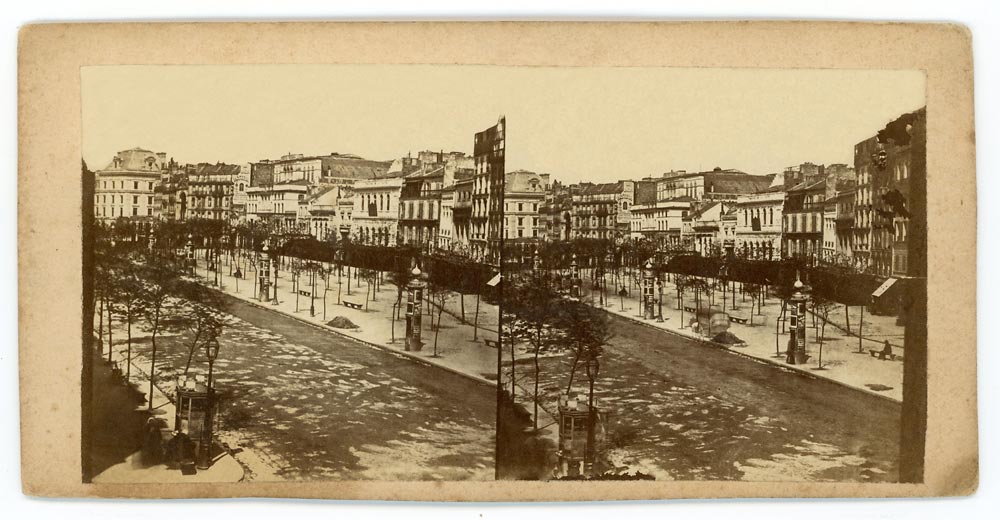

Fortunately for anybody photography made fast progress and soon stereoscopic images could be bought non just on plate merely also on glass and on newspaper. When nosotros await at those early stereos and compare them with what was written about them in the press at the time, we cannot only exist surprised past the discrepancy between the praises one tin read and the photographs we are viewing in the stereoscope. We mustn't forget, however, that for the Victorians any stereo was a good stereo every bit long as it showed some depth, whether in a portrait, a group, or a landscape. They had very few images to compare with and were satisfied with compositions which, to our modern eyes, practice not seem very impressive.

At the time, each half of the stereoscopic pair had to taken sequentially which added to the third dimension of the resulting image a fourth one, the passing of fourth dimension. It is possible to see in a large number of those early stereoscopic photographs that things have happened between the 2 exposures: people or horse-drawn vehicles have moved or vanished, expressions on people's faces have changed, the easily of clocks indicate a different time, shadows accept moved to the left or to the right, seeming to poke into or out of their source, movement has become blurred and crowds expect like ghosts. The latter were described in 1861 by American philosopher and essayist Oliver Wendell Holmes, one of the few people to accept written extensively about the experience of looking at stereoscopic images:

Where are all the people that ought to be seen here? Hardly more than than 3 or four figures are to exist made out; the remainder were moving, and left no images in this slow, old-fashioned picture […] Ghost of a male child with bundle, — seen with right centre only. Other ghosts of passers or loiterers,— one of a pretty adult female, as we fancy at least, past the way she turns her confront to usa.five Oliver Wendell Holmes, "Sun Painting and Sun Pic" in The Atlantic Monthly, July 1861, p. 18-19.

One of my favourite of these sequential images is a view of the Cluny museum in Paris which shows a carriage drawn past a black equus caballus on one half and, nearly at the same spot, a carriage drawn by a white horse on the other half. Some other very curious instance, among dozens of others, is a however life taken in a garden in which something seems wrong. It is only when you lot accident upwards the paradigm that you realise that in one of the pictures a wing has landed on the handle of the watering can but is nowhere to exist seen in the other one. That tiny insect causes a visual disruption which is in itself fascinating because although the optics do non really see information technology the brain perceives something is not as it should exist.

Roland Barthes was probably non thinking of stereo images when he claimed that, at the showtime of photography, "cameras, in short, were clocks for seeing"6 Roland Barthes. Idem., but the first cameras used to take stereos were but that.

A lot of people do not appreciate the changes that occur between the ii images in sequential stereos and it is true that sometimes they can be a bit besides much, similar in the case below, a scene in Berne, Switzerland, past French lensman Alexandre Bertrand. On the whole however, I find them very interesting to report on account of this fourth dimension they give to the image and the information they provide near the time that elapsed between the two exposures.

A substitute for the real thing

Travelling for pleasure in the Victorian era was only available to a small-scale wealthy portion of the population and was not without risks. It soon became evident that, thanks to the stereoscope, a large number of people who could non beget the expense of going on a Grand Tour, could at least buy stereo cards of the places they wished to visit. Past the end of 1859 well-nigh of the known world had been photographed for the stereoscope, even such mysterious lands as People's republic of china and Japan, and commentators insisted on the pleasure that could be found travelling to far away places without leaving one's fireside, even or especially when ane was feeling poorly. "Cheers to the portability of these small prints", wrote photographer Henri de la Blanchère, "the public like to travel quickly and safely to the familiar or totally unknown countries where the photographer takes them; they observe it all the more enjoyable equally the fatigue and the dangers are for others but the interest is theirs. The world will presently be fully explored, and it can be explored repeatedly without one's curiosity getting weary or satiated; nature is huge and, thankfully, the thirst for knowledge has no limits."7 Henri de la Blanchère, Monographie du stéréoscope. 1860. Affiliate 11, p. 19-20

Columnist La Gavinie, from the photographic journal La Lumière, was one of the many armchair tourists who took advantage of the stereoscope to go on dangerless journeys. After all he was on the payroll of the Gaudin firm to advertise their stereoscopic viewers and cards:

I have just taken a long trip through a stereoscope – I take successively visited the remotest corners of Greece and Egypt. The ill, and in that location are many of them this wintertime, must accept, like myself, been plentifully entertained past the magical musical instrument. Information technology played a great role in their recovery, and the cleverest doctors now prescribe it along with their medicine.8 La Gavinie. "Chronique" in La Lumière, 13 Février 1858, p. 27.

As more and more stereo photographs became available information technology became apparent that not only those binocular images could bring back fond memories of past journeys9 Charles Paul Furne and Henri Alexis Omer Tournier, La Photographie, Journal des Publications légalement autorisées. February 1859 but too that the illusion they provided was stiff enough to make the observers think they had actually seen the site or monument they were looking at, even if they had never laid eyes on it. The illusion was turning into a "memory", every bit Hermann von Helmholtz himself explained in his book Physiological Eyes:

[…] these stereoscopic photographs are so true to nature and so lifelike

in their portrayal of cloth things, that subsequently viewing such a picture and recognizing in it some object like a house, for instance,

we get the impression, when we actually practise see the object, that we

take already seen it before and are more or less familiar with it. In

cases of this kind, the bodily view of the matter itself does not add together

anything new or more authentic to the previous apperception we

got from the flick, and then far at least as mere form relations are

concerned.10 Hermann von Helmholtz, Physiologial Optics, vol. 3, p. 303.

Oliver Wendell Holmes was even more radical in his views when he wrote that affair was now no more than a mould and that stereo images could literally replace anything worth seeing:

Class is henceforth divorced from matter. In fact, matter as a visible object is of no great use whatsoever longer, except as the mould on which form is shaped. Give us a few negatives of a affair worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we desire of it. Pull information technology down or burn it up, if you delight.11 Oliver Wendell Holmes, "The Stereoscope and the Stereograph" in The Atlantic Monthly, June 1859, p. 747.

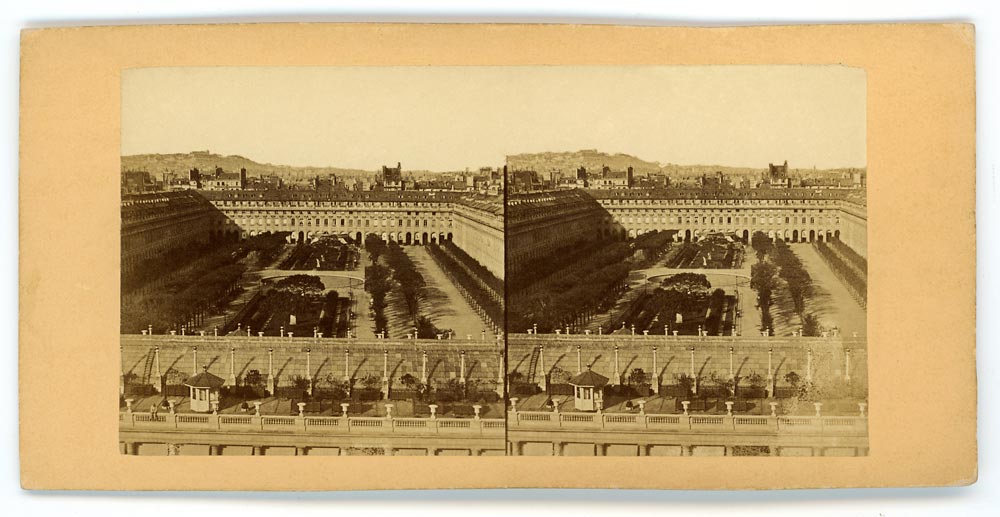

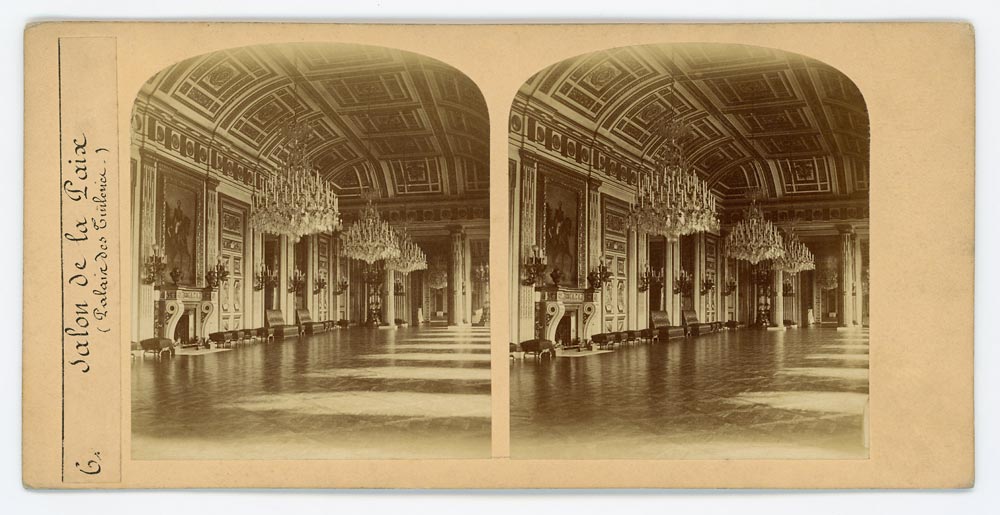

It unfortunately pleased the rebels of the District to prepare fire to the Tuileries Palace, which was completely destroyed in May 1871 and was accounted too potent a symbol of past monarchies to contemplate re-edifice. The palace, nonetheless, was extensively photographed for the stereoscope during the reign of Napoleon III so that information technology is still possible to get a fairly precise thought of its exterior and interior. There are actually and then many images that nosotros can well-nigh go through all the reception rooms – and even wait effectually them sometimes – from the Pavillon de Flore, next to the Seine, to the Pavillon de Marsan, along the rue de Rivoli.

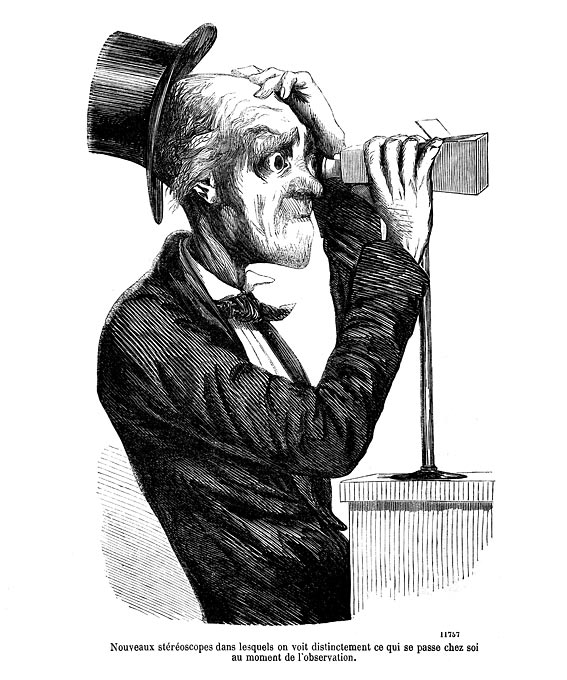

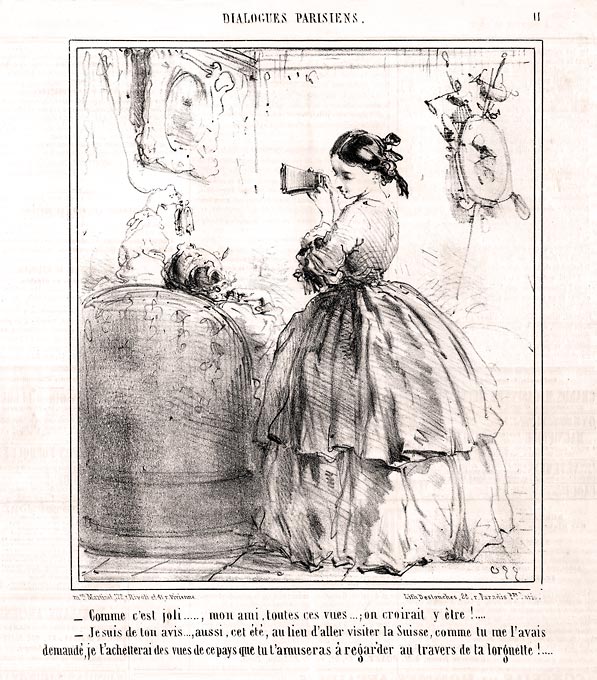

Gradually in the heed of amateurs of stereoscopic images the photograph came to be a proper substitution for the subject represented. This is clearly shown in the following lithograph by French creative person Charles Édouard de Beaumont (1821-1888) published in the satirical magazine Le Charivari on 24 February 1864.

- How pretty …. All those views …. ; 1 could almost imagine one was there ! ….

- I totally agree with yous … which is why, this summertime, instead of visiting Switzerland, every bit y'all expressed the want to, I will buy you lot views of that state and you will have a great time looking at them through your lorgnette ! ….

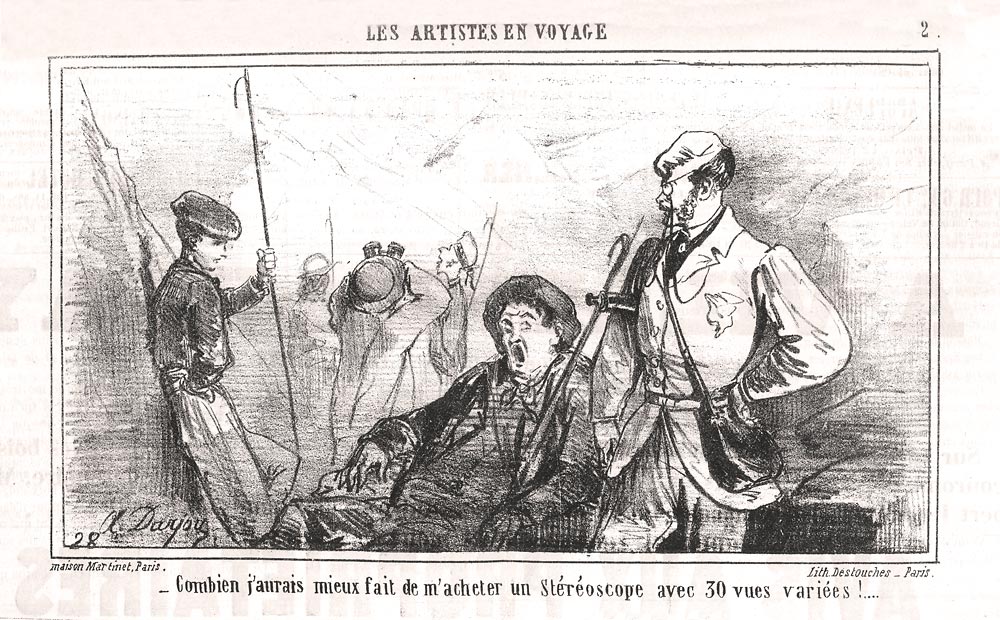

Another French cartoonist, Henri Alfred Darjou (1832-1874) chose to correspond an artist on vacation, tired after the twenty-four hours'south hike and wishing he had stayed dwelling house and taken his ongoing trip nearly.

– I wish I had bought a Stereoscope and a choice of 30 views instead ! ….

Fuel for the imagination

The Victorians loved stories and especially imagining new ones from a few given clues. It is no wonder the most popular paintings of the fourth dimension were of the narrative kind, a genre which gradually came to be considered equally also sentimental and has been looked down upon for far too long. Apart from a few famous canvases, like Henry Wallis's The Death of Chatterton, William Powell Frith's Derby Day, and a few others, these works are rarely studied or displayed any more than. Hundreds of narrative paintings, a lot of which unsurprisingly inspired staged scenes for the stereoscope which were hugely pop in their time, have been gathering dust in the storage rooms of museums and galleries, their current location a mystery.12 If you wish to know more nigh the connections between narrative paintings and the stereoscope read the book by Denis Pellerin and Dr. Brian May, The Poor Man's Picture Gallery, published past the London Stereoscopic Company. In the Baronial 1864 issue of London Mag of Entertainment and Instruction for General Reading, Leslie Walter tells a very foreign tale which only becomes clear in the last few lines of his text when we discover that the hero of the story has been dreaming after falling asleep over some stereo pictures brought to him by his nephews.

Here, accept away the stereoscope, my dears, and the pictures that I fell comatose over, after they had put so much folly into my old head. Put away the Spanish Daughter, and Dressing for the Ball, and that foolish, Moonlit Balcony, and the Sea-scene, and the Ball Room, and Mr. Fechter as Hamlet, and the Refusal, and the Young Lady with the Fan, and the other on an ottoman. Put the Helpmate at the bottom of the box, and the Bridegroom out of my sight; and that fine view of Madrid also, and the moving-picture show of a parlour; and heaven forestall my seeing again the Nice Swain, or the Pair of Lovers! I believe that was what did the mischief, after all.

There, put them all away, children, and never tell your aunt what nonsense your uncle talked in his slumber, later on seeing your stereoscope.

THE Terminate13 Leslie Walter, "In a stereoscope".Sharpe'southward London Mag of Entertainment and Instruction for General Reading, 25 (New Series): August 1864, pp.83-89

Stereo images did non have to exist staged, still, to have hold of the buyers' imagination, and start the narrative process. Oliver Wendell Holmes, in his iconic text The Stereoscope and the Stereograph, describes how details that could easily get unnoticed often get more important than the master bailiwick of the flick examined in the stereoscope, making the listen wander:

We have often constitute these incidental glimpses of life and death running abroad with us from the main object the flick was meant to delineate. The more manifestly adventitious their introduction, the more piddling they are in themselves, the more they take concur of the imagination.14 Oliver Wendell Holmes, Ibid, p. 745.

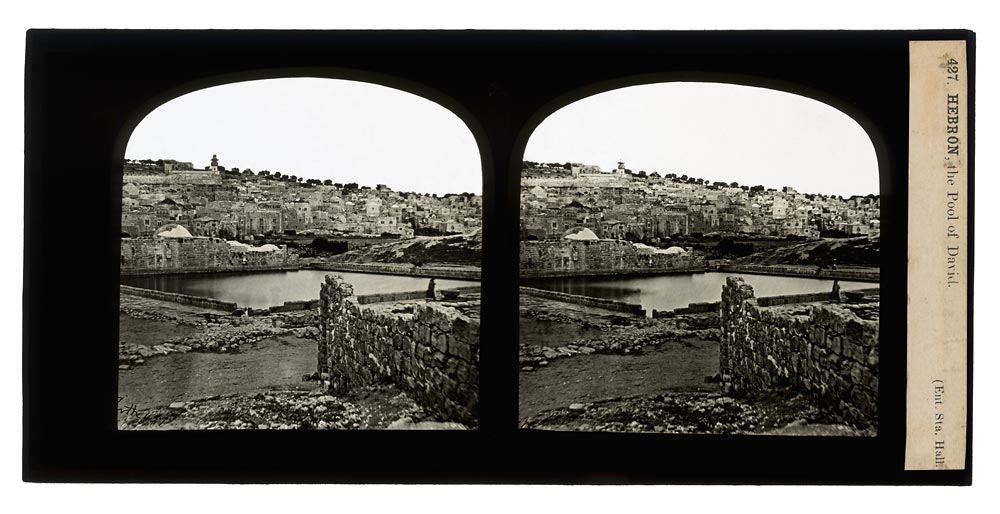

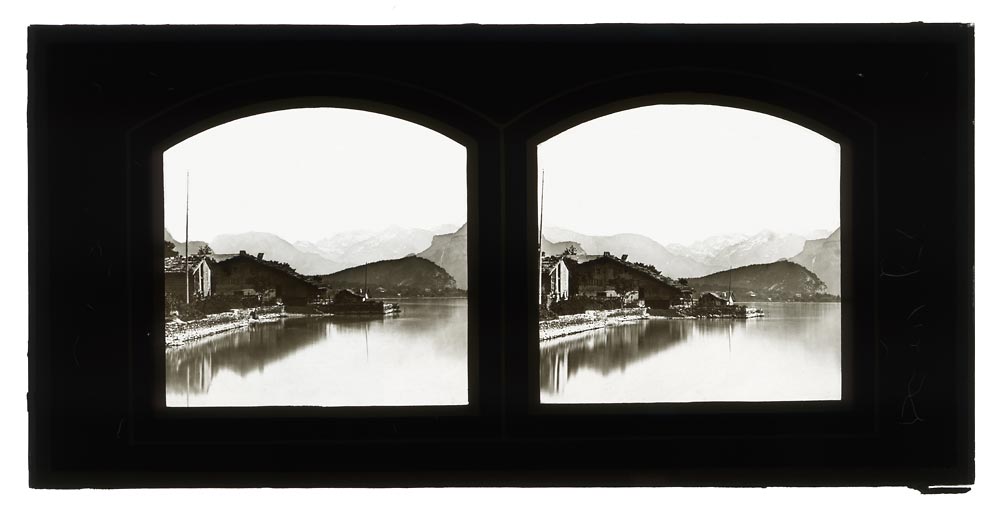

Looking at a stereo glass slide by Francis Frith showing the Puddle of David, at Hebron, then at a view of the Lake of Brienz by Claude Marie Ferrier, likewise on glass, the same Holmes cannot get his eyes off "a muffled shape" in one and "vaguely hinted female figure" in the other:

There is before united states a view of the Pool of David at Hebron, in which a shadowy effigy appears at the water's edge, in the right-mitt farther corner of the right-hand flick only. This muffled shape stealing silently into the solemn scene has already written a hundred biographies in our imagination.

In the lovely drinking glass stereograph of the Lake of Brienz, on the left-hand side, a vaguely hinted female person effigy stands by the margin of the fair water; on the other side of the picture she is not seen. This is life; we seem to see her come and become. All the longings, passions, experiences, possibilities of womanhood animate that gliding shadow which has flitted through our consciousness, nameless, dateless, characterless, withal more profoundly real than the sharpest of portraits traced past a human hand.xv Idem.xv

On the other side of the Swimming, poet Charles Baudelaire was describing something very similar while looking out over the roofs of Paris at a lit window. Isn't looking into a Brewster-type stereoscope a very like experience? Our eyes gaze through the darkness of a closed wooden box at an image which, illuminated as it is past the lite that comes through the trap door at the top of the musical instrument, appears every bit seen through a closed window (the window is definitely closed since we cannot touch the subject we are looking at however real and palpable it may seem).

Looking from exterior into an open window 1 never sees every bit much equally when one looks through a airtight window. There is nothing more profound, more mysterious, more than pregnant, more than insidious, more dazzling than a window lighted past a unmarried candle. What 1 can see out in the sunlight is always less interesting than what goes on backside a windowpane. In that blackness or luminous square life lives, life dreams, life suffers.

Across the ocean of roofs I tin run into a middle-anile woman, her face already lined, who is forever bending over something and who never goes out. Out of her face, her dress, and her gestures, out of practically aught at all, I have made upward this woman's story, or rather legend, and sometimes I tell it to myself and weep.

If it had been an quondam human I could take made upward his just as well. And I go to bed proud to take lived and to have suffered in someone besides myself.

Possibly you will say "Are you sure that your story is the real one?" Only what does it matter what reality is exterior myself, so long as it has helped me to live, to feel that I am, and what I am?16 Charles Baudelaire, "The Windows" in Le Spleen de Paris.

Below are the two pictures described by Holmes. By our modernistic standards they are far from outstanding and for nigh of us they would probably pass unnoticed or not be worth a second wait. Would you, reader, write "a hundred biographies" from the silhouette on the correct in Frith's picture or call up of "all the longings, passions, experiences, possibilities of womanhood" from the blurred shape on the left of Ferrier'southward image? I know I would probably non, at to the lowest degree not from these 2 images. Have nosotros lost that power of writing a story in our listen from a mere shadow? Have we been fed besides many "candy" narratives in the shape of TV series or films that few of us can practice what Holmes, Baudelaire and their contemporaries did so easily apparently? I wonder.

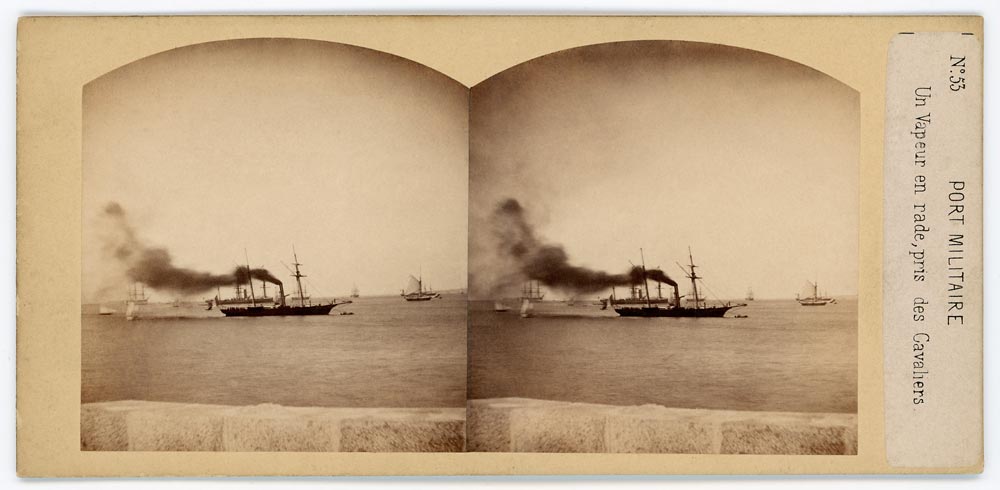

In case you might remember that only a human presence could trigger the Victorians' imagination here is another example not directly involving whatever men, women or children. This paragraph was written by Ernest Lacan, the editor of the photographic journal La Lumière, later on examining a series of stereoviews taken in 1858 at Cherbourg past Charles Paul Furne and his cousin Henri Tournier and published under the generic title Souvenir de Cherbourg:

At that place is amongst Mr. Furne's prints a true masterpiece: it is only the view of a steamer in the Cherbourg harbour. Is it arriving? It is leaving? Is it on its way to Kamtchatka, or getting back from Honfleur? Information technology doesn't matter; it is sailing and floating so lightly on the transparent sea, its masts are so coquettishly tilted, the smoke from its funnel is and so gracefully billowing, that our imagination feels drawn to it, and without further ado, we get on board and let ourselves be carried away towards the unknown, into the enchanted land of dreams.17 Ernest Lacan, "Revue Photographique" in La Lumière, 16 October 1858, p. 166.

Shortly after this piece was issued in La Lumière, one of Lacan'southward colleagues, a journalist from some other photographic periodical, Le Photographe, could not help exclaiming:

Speak of an amateur like Mr. Ernest Lacan to expect with the eyes of a poet into that and so unpoetical box which is called a stereoscope. Once the oculars of the musical instrument are close to his face, the witty editor of La Lumière does non but await into them with his eyes but also with his soul, his imagination and a petty of his heart.18 Le Photographe, xix novembre 1857, p.two.

Maybe nosotros should always follow in Lacan's footsteps and look at every stereo with our soul, heart and imagination if we really are to understand what the Victorians saw in them. One affair is certain: we mustn't gauge Victorian stereo images by our mod standards but try and empathise what their appeal was at the time they were taken, reviewed and sold, especially when they surprise u.s.a.. It is very frequently I find myself wondering while looking at a stereo card in the stereoscope: "Why on earth was this image taken? Who would buy such an prototype?". This is some other matter which bears keeping in mind at all times: if nosotros except commissioned pictures and amateur views (quite rare in the early days of the stereoscope), near stereoscopic photographs were meant to be sold. They were the offset mass-produced photographic images, several years before the cartes-de-visite and decades before the beginning postcards. Someone took those photographs with a commercial purpose in heed and to entice more than 1 person to buy so. There must, therefore, have been some appeal in every unmarried card on the market place. Sometimes we have lost the original references, the key so to speak, or we must accept that our tastes are different from our forefathers'. I know for a fact that I often find that Victorian humour leaves me indifferent or that comic songs of the 1830s-40s, even the most popular ones, fail to charm me.

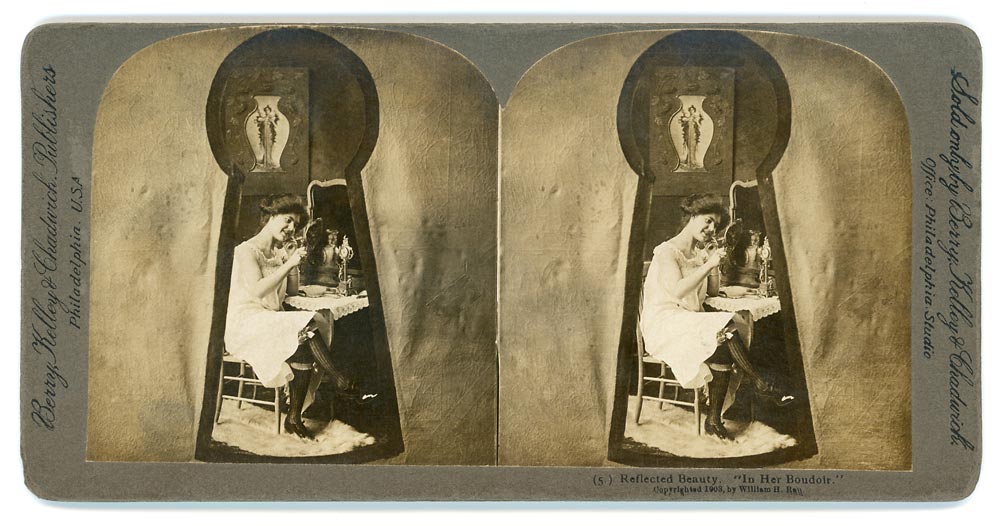

Voyeurism or "concentration of the whole attending" ?

Some modern commentators accept insisted on the voyeuristic nature of the stereoscope and the picture beneath, copyrighted by American photographers William Herman Rau in 1903, conspicuously shows that photographic artists were aware of the fact and used it to their advantage. At that place was a booming clandestine industry which specialised in the making of nudes for the stereoscope in the Paris of Napoleon Three and exported its productions all over the world. Despite the re-establishment of censorship, the fines and the prison sentences they received, a lot of photographers and female models institute this very specific co-operative of stereoscopy very lucrative and most of them bore the consequences with equanimity.19 Denis Pellerin has devoted a whole volume to stereoscopic nudes and what happened to the photographers and models who specialised in them. Called History of Nude in Stereo Daguerreotypes, Drove W. + T. Bosshard, information technology was published in 2020 in English, High german and French. The primary drawback of this state of things was that it gave the stereoscope a bad name which, to this 24-hour interval, has not been totally cleared.

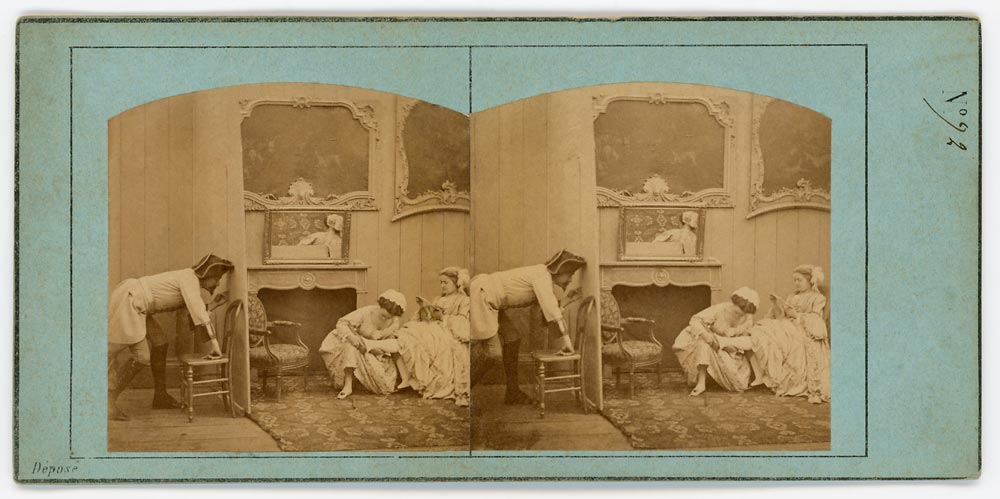

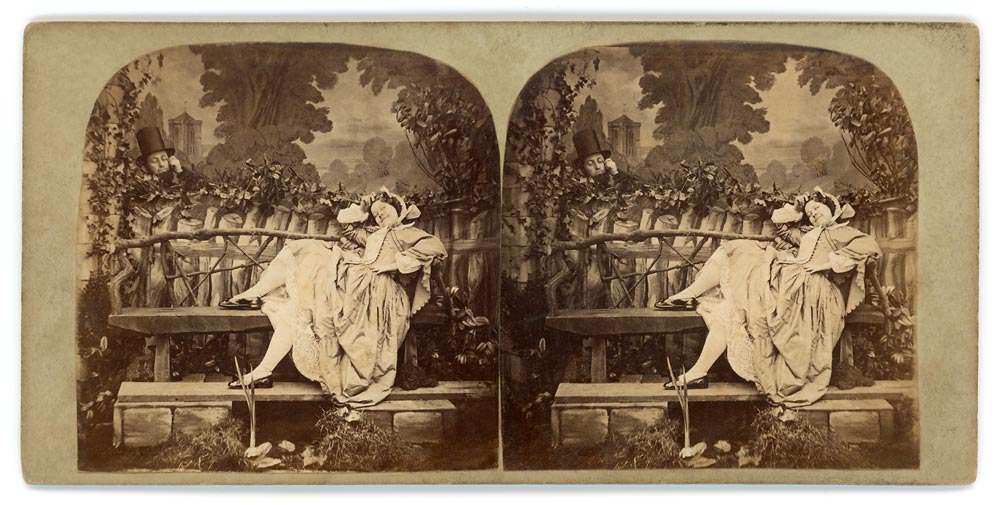

Even when stereo photographers were not featuring women in various states of undress, they notwithstanding managed to emphasise the voyeuristic nature of the stereoscopic observation in scenes such as the ones below. In both images we are looking at a man gazing at the ankles of a young woman (a highly erotic part of the female beefcake in the Victorian era), who is totally unaware of his presence. This could be called double voyeurism in a fashion since the stereoscopic observer can meet both the looker and the person looked at and even has a amend view of said ankles.

However, these images are not representative of the stereoscopic production and what could be termed a "voyeuristic gaze" for some was, for the majority of observers, more of a "concentration of the whole attention" which produced "a dream-similar exaltation of the faculties, a kind of clairvoyance, in which nosotros seem to leave the trunk behind usa and sail away into i strange scene later on another, like disembodied spirits."twenty Oliver Wendell Holmes, "Sun Painting and Sun Picture" in The Atlantic Monthly, July 1861, p. fifteen. (my italics)

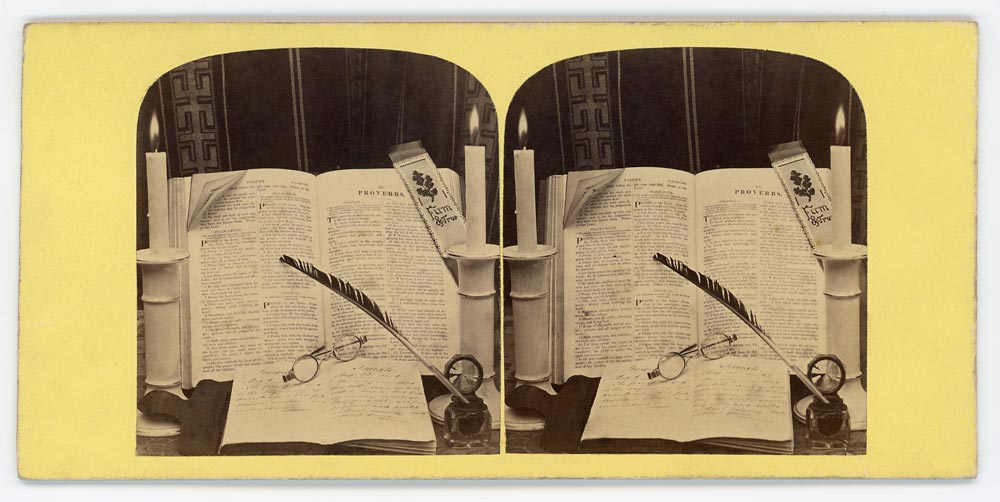

It would exist difficult otherwise to explain the being of dozens of pictures like the one below, featuring open bibles. These images are by and large to be found in Britain and in the States, two countries where bibles would, at the fourth dimension, take been found in the groovy majority of homes and were, for a lot of people, the only book that they would read. Why then would anyone take the problem of photographing an open book with some selected accessories (the most common ones existence a bookmark, candles, an hourglass, a pair of glasses, a magnifying glass, a glass of water, an ink well with a quill dipped in it, some flowers)? Who would buy them? My estimate is that, in a world which was expanding and with a footstep of life which was quickening, people felt the need for something to make them stop and introspect, something very similar in a way to today's meditation apps. These images suited that purpose perfectly. Once inserted in a stereoscope they became a sort of private and portable picayune chapel in which i was lonely with one's thoughts and one could concentrate on i's life and meditate on the words that could easily exist read on the displayed pages. In nearly pictures the bible is open up at dissimilar places, the Book of Isaiah, the Volume of Proverbs, or the Prophecy of Haggai, to name but a few, but the majority, however, characteristic some part of the Book of Psalms. This is definitely no voyeurism and totally a concentration of the observer's whole attending.

A personal note

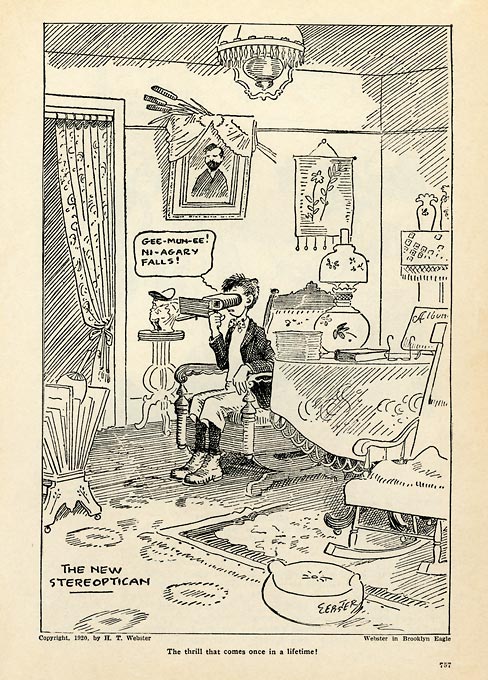

I have met people who, because they have seen a couple of hundred stereoscopic images, call back they know everything about stereoscopy and become cocky-appointed "experts" on the subject. I have been studying, researching and writing almost these images for over xl years; I accept literally seen millions of them in public and private collection; I think I know a thing or two most them and the people who took, published or distributed them, but there is even more that I practise not know and I certainly do not come across myself every bit an expert, just as a perpetual and apprehensive student on a never-ending quest (the best kind); in that location is not a calendar week that goes by without my finding images I take never seen before or coming across snippets of information that make me question what I thought I previously knew. The most of import thing, still, is that, after all those years, the magic is still intact and I feel the same elation when I insert a new image in the stereoscope and spend some fourth dimension exploring its various layers. I bought the drawing below very recently because it is e'er overnice to find new images showing people looking through a stereoscope. However, I don't hold with the caption which reads: "The thrill that comes once in a lifetime!" For me the thrill, thrills actually, come every single time I insert a card in a stereoscope. First at that place is a thrill of apprehension and and then, hopefully, comes the thrill of being drawn into the motion-picture show and of discovering another world. Ocasionally there is a third thrill, the one that comes when you unexpectedly observe an inscription, a particular that could non be seen in the flat carte, like Fenton'southward photographic railroad vehicle in a view published in the Stereoscopic Magazine, the face of a familiar model in a staged scene, etc.

I find all stereos interesting, to a signal of grade, and all stereograms, keen or shabby, should be given the chance to be free-viewed or examined in an appropriate viewer. And not simply once, for I hold with Oliver Wendell Holmes when he writes that "it is a mistake to suppose i knows a stereoscopic movie when he has studied it a hundred times by the assist of the best of our common instruments."21 Oliver Wendell Holmes. "The Stereoscope and the Stereograph" in the Altantic Monthly, June 1859, p. 744. Images that look grubby and faded have a way of "fixing" themselves when seen in a stereoscope. Our wonderful and malleable encephalon picks upwards pieces of data in each half and fuses them into something that is much more that the sum of their parts. But because we are not looking at the surface of the motion picture simply at something across it the grubbiness usually disappears, not completely simply enough to brand the paradigm more than appealing and to enable united states of america to find details which had been invisible earlier. And after all the grubbiness is part of the card's history. It speaks of all the hands it has gone through, of the parlour tabular array it has been lying on, of the soot that fell on information technology. Different framed photos and images stuck in albums and rarely looked at again, most stereo cards have had a busy social life and have been shared over and once more.

I have read a lot about the Victorian era and I guess it helps me empathise, most of the time, what I am looking at and appreciate the value of each image. Not the monetary value of course, although there are some very greedy sellers around who would have you believe that whatsoever stereo bill of fare which is more than 50 years of age is worth more than its weight in gold, just the historical, sociological or photographical value of the paradigm, the data information technology brings, the details it reveals, its composition along the depth axis, or the simple stories information technology often tells about the subject area photographed and, occasionally, about the photographer. At that place are still plenty of occasions when what I am looking at baffles me and I wish I could become more clues from the view itself or from the faces of the people I detect there. If stereos could speak ! How much more would be understood about these fascinating images. Since they cannot, we must keep looking for more clues, more information, more facts, publish more articles, more books, because, from fourth dimension to time, something comes upwards that adds a piece to this gigantic jigsaw puzzle. Can I feel stereo cards the way the Victorians did? I don't think and so, only I strive to find some tips in the writings of the time that tin can help me improve understand their state of mind, what fabricated them tick, what captured their attention and grabbed their imagination. I keep trying and will keep on doing then. And in the concurrently, I can only 2d Oliver Wendell Holmes' passionate declaration:

Oh, infinite volumes of poems that I treasure in this small library of glass and pasteboard!….22 Ibid, p. 745.

0 Response to "Photographie Ã⠠Paris Stereoview Paris Au Stereoscope"

Post a Comment